NP: To P or Not to P? (P vs. NP Explained)

Imagine a world where computers can solve impossibly difficult problems with ease. In this world, we have algorithms that can tell almost instantaneously whether you have cancer, just by analyzing a blood sample and your DNA. On the very same day that you are diagnosed, an algorithm will be able to compute the encoding of the protein that can treat your individualized cancer mutation. You take a pill and you will be cured within days. In this world, passwords, pins, and secret keys can be cracked almost instantaneously with an algorithm. We have no credit cards, no encryption across the web. Privacy does not exist!

This is a small peek into a hypothetical world where P = NP, one in which there are algorithms that can easily solve problems we consider today to be extremely difficult. Does P = NP? Do we live in such a world where these algorithms are out there, just waiting to be discovered?

This is one of the great open problems in theoretical computer science. It is also a million dollar question; the Clay Mathematics Institute offers a cash prize to anyone that can prove P = NP to be true or false. But most people believe that a proof can never be found.

Personally, I am both excited and alarmed by the thought of a P = NP world. But I’ll leave it to you to decide what to believe.

Sooo...what exactly are P and NP?

P represents a set of questions that are “easily” solvable by computers, and NP represents a set of harder questions, ones that cannot be easily solved.

An “easy” problem for a computer to solve might be something like adding two numbers. We can reasonably assume that with sufficient computing power, we can do this fairly easily for larger and larger numbers, since we have a known formula for adding two numbers.

A “hard” problem might be something like this: given 100 cities in the United States, find the shortest route that hits all 100 cities and returns to its origin city. Can you think of an algorithm for this? There are 100! possible routes that could be taken. This number looks something like:

93326215443944152681699238856266700490715968264381621468592 …

Well, you get the idea! It has 158 digits in total - the number is approximately 9.33 10^157. To put this in perspective, the age of the universe (13.7 billion years) in seconds is 4.32 10^17 seconds. Imagine a computer crunching through all of those routes. Even if it took a millisecond to process each route, it would take much longer than the age of the universe to solve our problem! And imagine if our problem called for 1000 cities. Or more. It’s intuitively clear that this problem is not so easy for computers to solve.

Factorization is another “hard” problem: given an extremely large number x, find the two prime factors that multiply to x. One approach is to try every possible factor of x, namely all the numbers below its square root. This may seem naive, but it is actually our best known approach. In modern cryptographic systems, we use extremely large numbers as public keys to encrypt messages, and prime factors as secret keys for decryption, relying on the assumption that factoring large numbers is a “hard” problem.

We have built many systems around the idea that “hard” problems are, in fact, hard to solve. But claiming that P = NP is the same as saying that there is no real distinction between these “easy” and “hard” problems. If this were actually the case, our privacy systems would fall apart!

And now the fun part: math!

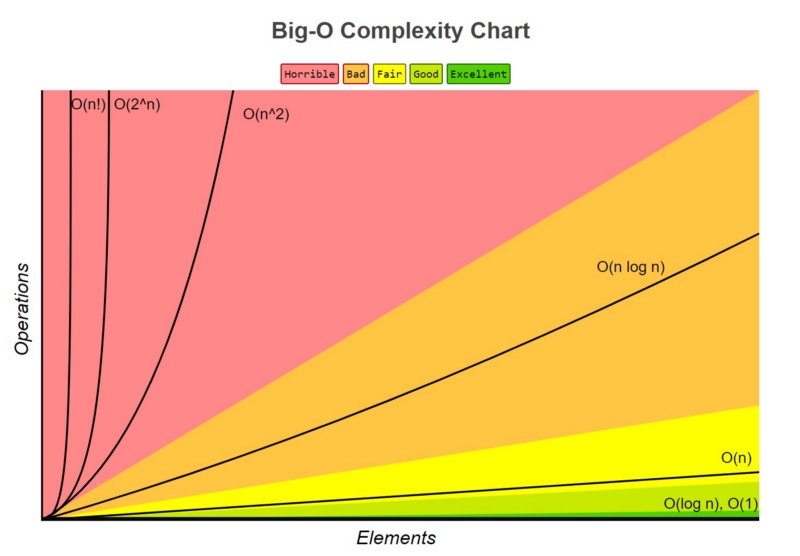

Just kidding, no math. At least, not too much of it. We are going to throw in a few mathematical definitions of P and NP to understand the problem in formal terms of computational complexity. People that do computer science like to define “easy” and “hard” within the context of runtime, so we will dive deeper beyond our earlier definitions of P and NP as simply “easy” and “hard” problems.

P stands for “Polynomial Time”. This means that it is the set of problems solvable in polynomial time, which in turn means that the runtime of the solution will be some kind of polynomial: if N denotes the input, algorithms that solve any P problem will have runtimes like N^2, N^3, etc.

NP stands for “Nondeterministic Polynomial Time”. This set of problems cannot be solved in polynomial time; they will take longer, for example exponential time. However, given a solution to an NP problem, a computer will be able to verify in polynomial time whether that solution is correct. Specifically, these problems are “decision problems”, ones that have yes or no answers. So, NP is the set of decision problems for which a “yes” answer can be verified in polynomial time.

Let’s summarize.

Based on these fancy definitions above, we can now rephrase the P vs. NP problem: if it is easy to check that a solution to a problem is correct (verifying an NP decision problem), is it also easy to solve the problem?

Back to the Traveling Salesman

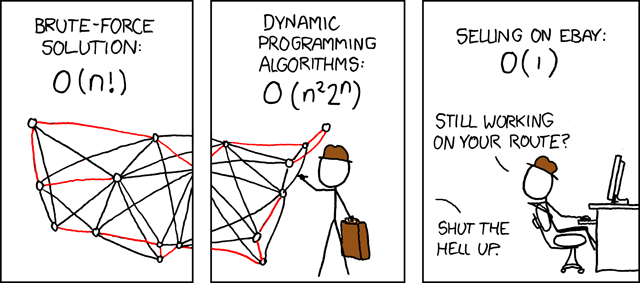

Let’s revisit the first “hard” problem we talked about: finding the shortest route through 100 different cities. This is a well-known problem called the Traveling Salesman, and we can rephrase it generally. Given a list of cities and the distances between each pair of cities, what is the shortest possible route that visits each city and returns to the origin city? We concluded earlier that a simple solution for this is not readily apparent.

But we can rephrase this as a decision problem: given a list of cities and the distances between each pair of cities, determine whether there is a route visiting all cities with total distance less than some value k. In this case, we can verify whether a solution (a given route) is correct by summing the distances between cities in the route and checking whether the total is less than k. This decision problem is in NP because verifying whether a solution is correct takes polynomial time.

To actually solve the TSP decision problem rather than just verifying a “yes” solution (also called a certificate), we would have to run through a series of brute-force guesses:

- From a city A, we “guess” the next city B to visit.

- If a path does not exist between cities A and B, we stop traversing.

- When we have traversed each city, we check whether the total distance of our route is less than k.

- Repeat for all possible combinations.

We can recall from earlier that there were 9.33 * 10^157 different possible routes for a TSP with 100 different cities. Imagine the number of routes we’d have to brute force as the number of cities scaled! We can intuitively see that this would not run in polynomial time. As it turns out, for all NP problems (as far as we know), brute-force guessing is the most optimal algorithm for a solution.

Here lies the intuition for P != NP. Checking a certificate is relatively simple and fast. Arriving at a solution in a systematic way - not so simple or fast when the known optimal algorithm relies on trial and error guessing.

Final Thoughts

My favorite aspect of P vs. NP lies with its irony: the question itself is a hard decision problem that we could verify a solution for, if only we had one. But P != NP implies that we couldn’t find one. And we are unable to prove this “no” answer, even if we could verify a “yes” answer - which would require a solution that we probably cannot find!

So, P vs. NP remains an open question. It is possible that a fast, polynomial time algorithm for NP problems is out there, and we just haven’t yet discovered it. And until we do, we cannot prove P vs. NP one way or the other.

Resources and Further Reading

- The Golden Ticket: P, NP, and the Search for the Impossible by Lance Fortnow

- Scott Aaronson’s research papers and blog posts

- A fun Youtube video overview